From His Only Daughter

In thinking about my dad these past few years I came to the unhappy and disappointing conclusion that I didn’t know him at all. We visited London once when I was about eight and he excitedly showed us his old haunts and babbled on with stories about his time there. I was bored and didn’t listen to a thing he said because I took for granted the fact that he’d be around to re-tell those stories if ever I was interested.

My mum’s friends and my dad’s friends were quite different and they only had a handful of mutual close friends. My mum is a great connector of all the people in her life and so I’ve always been highly familiar with her friends and family. Daddy was awful at keeping in touch with anybody, but he could pick up without missing a beat with any of them regardless of how many years had passed since their last meeting.

I don’t know if he purposely wanted his family and friends separate or if it just turned out that way, but that’s how it felt with Daddy: separate. Though, I remember when we were in Dubai my parents would have dinner parties where my dad’s co-workers from the newspaper and other miscellaneous friends of my parents’ would show up. There would usually not be any children save my brother and myself and we’d busy ourselves with our playthings in the other room. I don’t know what all was discussed, but there was always tons of laughing and a wonderful atmosphere of a good time being had. We had similar gatherings far less frequently and on a much smaller scale in Canada, perhaps because my dad’s better friends all remained in the Middle East. Currently I have very few people who personally knew him to regale me with stories of his youth, or even his time in Dubai, Karachi or Toronto when I was too young or arrogant to care if my father had led an interesting life prior to my birth.

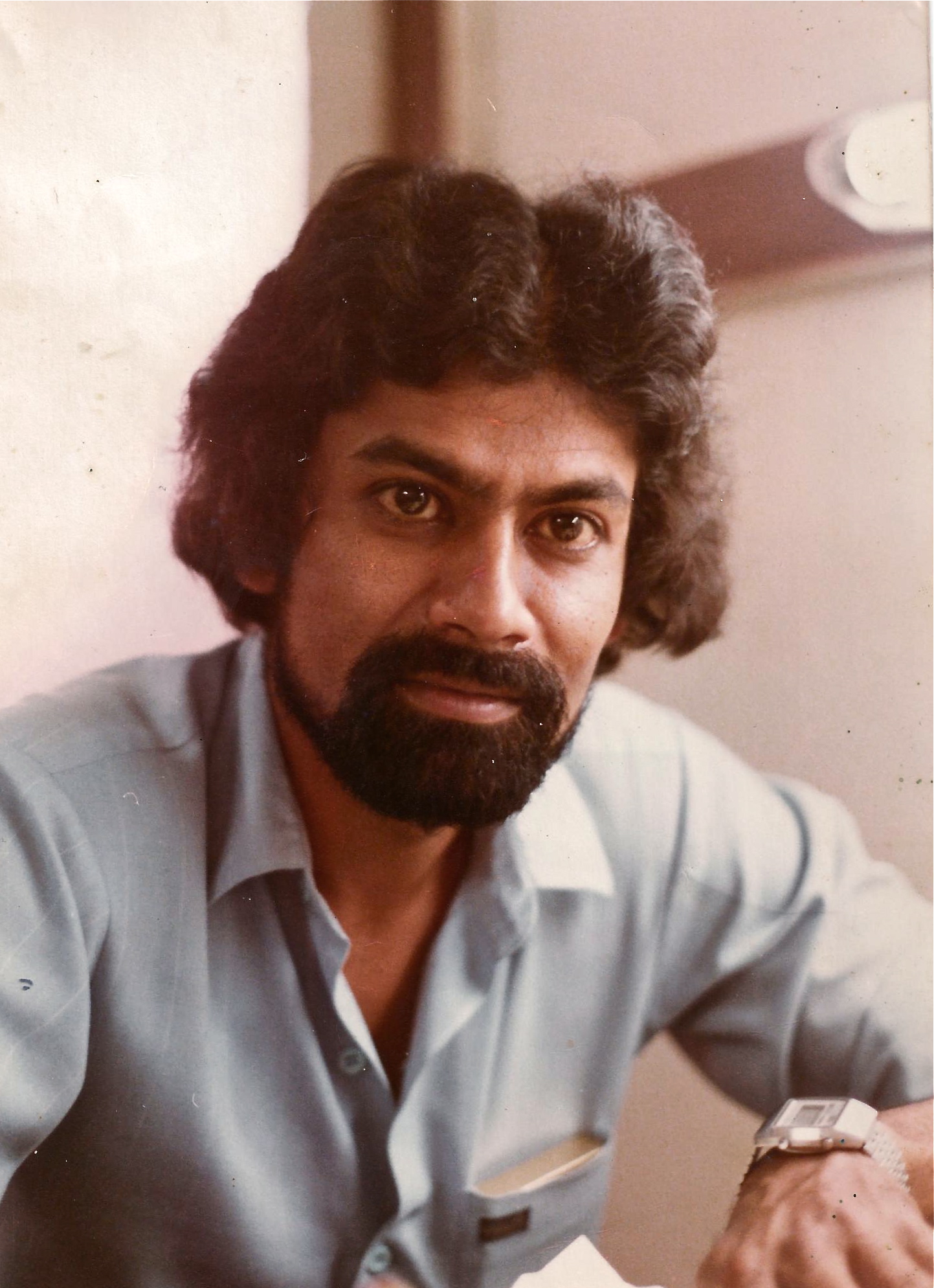

Daddy collected a pile of photos from his time in Europe and a handful from his own youth which I have stolen away from my mother. Initially I had done so for a photo project after which I returned them, but then I stole them again feeling they should be my property because I’m the most curious and without answers. The photos illustrate events and outings he had with friend in London and Italy predominantly. Some of them stir a devious envy in me where I yearn to have the impulsiveness he possessed rather than my mother’s sense of practicality. For the last couple of years there has been a sense of unrest within me that is encouraged by repeated viewings of these photos from which emits a sense of utter carelessness and serenity.

I know those days weren’t all fun and games for him; I’ve heard scraps of tales of his hardships and heartbreaks there and though this allows me a better idea of his experience, I know that there is so much more still being kept from me. The problem is that I’m not sure if it’s purposely being kept from me, or that there’s no one around to tell it to me. I’ve attempted (feebly) to contact people in Daddy’s life, some of whom I only vaguely remember and others who I’d never heard of before, to find out more about his life. I’ve had little to no luck as, unlike my dad, I was never any good at striking up friendships.

***

The thing I probably most regret is that I haven’t any photos of Daddy that are my own. Photography didn’t become a properly invested-in hobby until the very end of university, long after Daddy’s passing. My mum was always an amateur photographer, but her photos are very organized and intentional. I enjoy the natural poses or candid shots and think of a photograph as an exact documentation of what my own eyes see. I’ve a perverted fear of being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and not being able to remember anyone or anything, so I take photos to remember just what I saw as I saw it. Until recently, I also used to keep incredibly detailed journals for the same reason, although at the time unbeknownst to me.

Now, I’m plagued with the inevitable possibility that I will grow older and forget what Daddy looked like. My memories with him can (and will be) stored in my writing as well as by my constant retellings to whomever will listen, but his face is harder to describe and soon I will forget it as I saw it and have only my mum’s posed photos to assist me. I’ve already forgotten what he smells like: I used to be able to recognize it when I smelt it, but I can’t really even do that anymore. Next his voice will start to fade and soon his whole face.

I’m most worried that if I have kids I’ll be unable to answer their questions about their grandpa. He’ll just be another dead ancestor to them and that pains me, especially if, by some sad twist of nature, a dormant trait that skipped my brother and myself shows up in them: something so acutely Daddy that I won’t know weather to be glad or torn up about it.

I’m not one to have regrets ever because I believe everything happens for a reason, but I do resent the fact that it took me so long to love photography. I wish I could have either experimented earlier and used my dad as an occasional model or that Daddy had lived just a few years longer so I could’ve taken at least one photo of him myself, which I could look at and say “Yes, that’s exactly how I remember him.”

***

He wrote a semi-autobiographical novel and I was assigned to edit it. At the time this task was one that made me boast my importance as a fiction and writing connoisseur, but it was still a chore. Thinking back I’m touched by his confidence in me considering I was only seventeen or eighteen at the time. When he passed, many people (myself included) joked that I should dig up this novel and edit it and attempt to get it published in his honour. I don’t know but I think I was the only one who was even remotely serious about this idea. I still think about it, but have yet to attempt it mostly because I spent so much time running away from the fact that he had passed and anything with which he was associated. Now, it just gives me a strange feeling thinking of altering the last thing he ever worked on.

A few months after his passing, I took a hiatus from writing. I had been regularly submitting stories to a local university magazine which entertained a different theme every month. I found I was starting to write for the magazine just to get published and, young and proud as I was, I decided that if I wasn’t going to write for the love of writing, then I wasn’t going to write at all. It was possibly the worst mistake of my life as writing has been something I have done since my fourth grade teacher, Ms Kitagawa, opened my eyes to the prospect of a writing career and encouraged me enthusiastically. Daddy soon became my number one fan, embarrassing the hell out of me by praising everything I wrote and emphasizing how he wished he could create fictions with such ease. I haven’t heard praise like that about my writing in half a decade and I miss it more than I can tell.

The Boy has since taken up the post of my number one fan and I refuse to be embarrassed by it. When I’m not writing I feel like I’m waiting at a bus stop with a full day of errands, and no bus in sight. It’s demoralizing and leads to severe apathy, a cloudy head and a distinct feeling of “Life can’t get any worse, so what’s the point?” It took a damn long time, but I’m writing again and I feel like you do after a really good workout: refreshed, energized and ready to tackle everything I’d previously been avoiding. It irked me that I’m not doing fiction, but I’m writing what I know and all I’ve known recently is that I’ve realized too late all the things I’m going to miss sharing with my dad. I feel like I’d done him wrong by not mourning at his funeral nor for years after, but that can’t be helped anymore.

I wish I could share with my dad my personal accomplishments the most: getting my degree, becoming fluent in Spanish, working for a magazine, exploring photography, finding love, writing and (when it happens) finding peace. I also, one day, hope to be able to listen to Simon & Garfunkel’s “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” watch Peter Sellers in The Party, visit Italy and read his novel without feeling a twinge of sadness and loss, but only pleasure at having once known him.

***

My mum once mentioned that when they were first married, my dad would attempt to impress her by telling her how much like Woody Allen he was. To Daddy -- a great fan of Allen’s -- this comparison was the ultimate compliment. I didn’t discover Woody Allen until I was in my twenties, so I was never able to discuss his movies with my dad; therefore I don’t know which were his favourites, or why he loved them so much.

In my head, once upon a time, Woody Allen always reminded me of my dad, though I knew nothing about him except that he was a filmmaker and actor. Then, during my later university years Woody Allen was the only person in the world who understood how I felt and what I thought. Now, Woody Allen is one of the few people who “gets” me and whose movies I introduced to and love watching with the Boy. It’s beyond frustrating that the only time Woody Allen was associated with my dad was before I knew anything about either of them. Today, I think I know more about Woody Allen than I do my own father.

I was not close with my dad or mum and after Daddy’s passing a fork was wedged between my brother and me, as well. The result of this is my continuously growing knowledge of movies, books, pop culture and the histories of all three, but no one to share them with. It now feels that Daddy was the one person who existed to care about my overflowing trivia since it was almost always on topics of which he was extremely fond.

Save for a brief stint as an aspiring screenwriter/director in high school I’ve never looked at movies from an artistic viewpoint. They’ve always been there solely for my entertainment and to allow me to escape whatever problems plague my life at any given time. While they’re solely an escape, they are also an integral part of my life and a ritual of sorts. People who have gone to the movies with me know my idiosyncrasies regarding seating, theatre, time of week and even time of day; watching a movie at home comes with rules, too. The cinema is a wonderful treat every single time, no matter if the movie is good, bad or one I’ve seen countless times. Film is such a major staple in my life and I can’t really pin point why, but the more I think about it, the more I wonder if Daddy would’ve been the one to be able to explain it to me, perhaps because he, too, felt the same. From what I remember, Daddy absorbed movies, but did so in a way where I never fully grasped the depth of his experience with the medium.

I know Daddy reviewed movies for a newspaper when I was a child, but I never got the chance to talk about film with him. But I watched and subconsciously learned that he breathed film. When the Khans lived in Dubai my dad was friendly with a local theatre manager, so we’d sometimes get free admission to the movies. Often times these movies were not really suitable for kids (I remember being bored to death through Money Talks and Teen Agent [which was alternately titled If Looks Could Kill]), but other times they were good fun for the family. I recall us being treated to a Jim Carey double feature on a whim where we saw The Mask and Ace Ventura: Pet Detective and for months after my brother and I would mimic the Mask’s trademark sayings and catch phrases with my mother joining in and egging us on. We watched Speed and I became obsessed with it and drilled my dad for the names of the four lead actors. I think they were the first English-language actors I knew by name and my mum would shoot questions at me which I would answer eagerly and proudly, as if on a quiz show.

I remember my dad (like me) loved television, too. He was always watching something and I used to envy him staying up to watch all he wanted while my brother and I were sent to bed. Sometimes, I would meander into the TV room after a late night trip to the bathroom while he was watching and catch sight of a movie he stopped to watch. Daddy always stopped to watch scenes from movies he’d seen and loved (as I also do). One time he happened to stop at a scene from Blake Edwards’s The Party. It was the scene when Peter Sellers’s character is feeding the parrot and reads “Birdie Num Num” on its food bowl. Sellers’ pronunciation of “Birdie num num” in that thick, Indian accent of his sent me into hysterics and my dad was equally amused both by Sellers and my reaction to this bit. From then on it was sort of an inside joke with us. We would mimic Sellers and laugh at ourselves and the memory of the scene.

I didn’t watch the rest of the movie then, but I did years later and many times after that. That scene still makes me laugh out loud, but the fact that I can’t go find Daddy and relive the scene with him breaks my heart. One of the first devastations in my life was to know that I had grown to love too late something my dad had also loved; thus making it impossible for me to ever love it with him.

Daddy was known to openly weep during sad movies and even TV shows and my mum used to tease my dad for being such a sap. My favourite anecdote is one my mother told as a snarky comment about how Daddy used to cry while watching Little House on the Prairie. My brother and mum are not ones to be touched by fictional hardships, but I always have been and I guess I got it from my dad. When E.T. was re-released in theatres, the Khan family went to watch it together. We’d all seen it previously, obviously, but my mum still likes to poke fun at the fact that by the end of the movie Daddy and I sat trying to hide wet, tear-stained faces unsuccessfully. To be fair, I never saw Daddy cry in my life, but I hope he did cry during that screening of E.T. and I hope he did used to weep watching Little House on the Prairie so that I can still feel like his daughter even while he’s not around.

***

Long ago I claimed the one thing I wanted each of my parents to leave me after their deaths. From my mum I wanted her massive collection of family photographs and from Daddy, his books. Being truly my father’s daughter I adore books, sometimes more than reading itself. When I was younger and before I could afford to buy my own books, my dad’s collection was the largest private collection of books I’d seen. It’s never been a huge collection and probably contains less than twenty-five percent of the books Daddy had actually read in his lifetime, but to me it was the greatest.

Daddy was the one who got my brother and me our first library cards and since then I’ve depended on the Toronto Public Library. I was never one of those people who prefers to own every book she reads nor do I fuss about my books remaining in pristine condition. The majority of my books are bought second hand and the more yellow the pages, the better. I love library books because almost every book from the library has been well-loved and well-enjoyed, which makes it special to me, for some reason.

The Boy is one of those people who has a pristine collection of books that look untouched (even his second hand books have a standard) and I am not allowed to borrow any of his books, ever. He would rather buy me my own copy than lend me one of his. I pretend to be hurt by this, but I understand his apprehension because Daddy was also a nut about his books.

It was all his things, actually. Daddy’s one rule (which I find I also live by) was that you were free to borrow any of his things on the condition that he never find out about it. This meant everything borrowed had to be returned in a timely manner and in the exact same condition. We all thought he was an old grouch and a miser about his things, but the older I get and the more things I acquire, the more I see the usefulness of this rule. Daddy was always reluctant to lend out his books to my brother or me to the point where if ever I needed or wanted to browse his books, I had to force myself to handle them as if they were a precious object. I still do this with Daddy’s books, though I no longer know if it’s done because his books are all I’ve left of Daddy or it’s a habit carried over from my childhood.

I took for granted the diversity of Daddy’s collection and only now realize its importance. His collection holds books in all sizes, colours and subjects. He studied philosophy in school, had a passion for film, read Urdu poetry and most classics, to name a few. He had a number of dictionaries, as well, for at one point in his life he had been multi-lingual having spent some of his youth living in Europe. As far as I know, he was once fluent in Urdu, English, Persian, French, Spanish and Italian. There could be more, but those were the ones I knew of. By the time my brother and I were starting to learn French, Daddy’s French had deteriorated so much that he was unable to help us with our homework. I’m told his fluency in most of the other languages continued well into his later years, though.

***

When we were younger we’d beg Daddy for a bedtime story. He would always say he wasn’t good at making up stories on the spot, but we’d say we didn’t care and insist on one. So, he took to retelling famous novels as bedtime stories. The first one I remember he had described as a story he’d once read and it turned out to be Gulliver’s Travels. A few years later when I saw the book on his shelf I was awed in that way children get awed when they notice a link between their own personal lives and the life of the world. Another book he’d tell as a bedtime tale was The Little Prince and he would even, at my insistence, make the drawings of the elephant and boa constrictor at the start of the book.

Apparently, my favourite of all his bedtime stories had been one he himself had heard as a child, if I’m not mistaken. Unfortunately, I cannot for the life of me remember what it was called or what it was about except that it involved some farm animals (sheep, maybe?) and a wolf. Daddy told it to me in Urdu and I apparently used to love it and request it more than any other story. I wish I could at least remember the name of this tale.

***

Like most kids in university, I started reading Kurt Vonnegut. While Slaughterhouse-Five didn’t have an affect on me Breakfast of Champions impressed the hell out of me. Surprisingly, Daddy had never read Vonnegut, so I lent him my copy of Breakfast with enthusiasm. He read it and loved it and I was so proud since this was the first time I’d introduced my well-read and well-traveled father to an author. He asked for more Vonnegut if I had it, but I didn’t. For his following birthday I got him a copy of Jailbird and he was delighted. He never got a chance to read it, though.

***

Daddy was never one to withhold his opinions even (or especially) if they were controversial. He loved debates and discussions and, I don’t know if it was on purpose or if he was just being difficult, but he always challenging everyone’s ideas and beliefs. Once my friend Subha stayed for dinner and the conversation suddenly became a debate with Daddy claiming that Shakespeare was over rated and Subha and I fiercely defending the bard. I remember being mortified that my own father had such unconventional views on something that was inarguable. Later on when we were both in university, Subha said to me that she thought my dad had been right after all. This was no great surprise to me as I, too, had since developed my own opinions and ceased to borrow others’.

He had views on religion, as well, of course, and they were predominantly against it. My mother is a practicing Muslim and has been for as long as I can remember, but I’d never seen Daddy do anything even remotely religious. In fact, while my mum would answer our questions about God and Islamic practices, when asked, Daddy would challenge these answers which we robotically regurgitated. He would ask simple questions, like challenging the existence of God, and my brother and I would attempt to answer. He never really argued back, but the fact that he questioned it at all was a whole new perspective for us, though we didn’t realize it at the time. My mum and dad had been married for years with fiercely opposing religious views, yet lived peacefully together and this has always been my idea of how the world should be: all different, disagreeing, conflicting views living together harmoniously.

I didn’t know it then, but that is how both my parents taught us that personal beliefs are just that, personal. They’re not to be inflicted onto others nor used to insult others’ beliefs. I strongly think that this is the reason why I am able to sympathize with the religious and non-religious alike and only butt heads with those who insist on publicizing their private beliefs. I’m glad that my dad was the sort of man who questioned everything, even if that was considered taboo, because it made my brother and me better human beings.

***

There are other, less important things that I regret not being able to share with him, too. I’d love for the Boy to have met him, partially because I’m proud that I can call him my partner, partially because I’ve told him so many stories about my dad, but mostly because they would’ve gotten along so well that it just seems so unfair that they’ll never meet. Most people don’t appreciate their parents until adulthood, so more than being angry that I lost him when I was still unable (or unwilling) to appreciate him is the fact that I’ll never get a chance to let my dad know that I do, finally, appreciate him. So much so, that I almost hate him for dying and changing all our lives forever.

Unlike most people who fail to remember (or acknowledge) the downfalls of the dead, I refuse to let myself forget his annoying and unattractive habits. Though he taught us what sort of human beings to be, he also taught us what sort of human beings not to be, which is equally important. Daddy was infuriating: he was often short with my brother and me and supported a direct order with “Because I said so.” He smoked and in the later years we even ganged up on him to ban smoking indoors, but this soon failed because he started flat out ignoring us (though he did cut down the smoking considerably). He drove like he was being chased by the law, couldn’t help but flirt with any and every waitress around and often preached to us what he did not practice in regards to smoking and drugs.

Being mainly under the influence of my maternal family, I looked down upon things like drugs, alcohol and sex for many years, but then realized that to hate those things and the people who did them was to hate my own father and that couldn’t be right at all. Daddy wasn’t an alcoholic, drug addict or sex fiend, but he did enjoy all those things in moderation throughout his life. Daddy unintentionally forced us to be tolerant of what we don’t support ourselves. The flirting he always did was funny when we were kids but grew embarrassing when we were teens. Ironically, I find I’m also a natural flirt when I see anyone even remotely attractive and the Boy is actually an even bigger natural flirt than I.

It’s no surprise, then, that I would love go out for a family dinner and have him casually flirt with the waitress, or have the smell of Dunhill cigarettes in the living room again, or go on one of our memorable family road trips where my brother and I watch amused as he speeds from border to border while my mum prays profusely for our safety in the passenger’s seat. I think if you fail to remember the imperfections then you fail to remember the person and begin questioning why such a great man had his life cut short. Well, my dad wasn’t a great man: he was just another guy. The only thing that makes him any special is that he is the only dad I’ll ever have and I’m glad to be his only daughter.